Reading Room

Reading Room

IRIG IN SERBIAN LITERATURE AND VICE VERSA

A Pinch of Srem Spice

Last year, while creating a monograph about this small town and municipality, we compiled an anthology titled ”Irig in Literature”. In it, you can find a song from Zmaj, some prose pages by Milorad Popović Šapčanin, a text by Jovan Grčić, and a description by Crnjanski. Essential were the adorned writings of Dositej Obradović, then Vrdnik diaries by Milica Stojadinović Srpkinja, and Mihiz’s chapters from Irig. Step by step, it grew into a book. While waiting for that book, we will share with readers some Irig fragments from these last three

By: Bane Velimirov

We stopped by this town this summer for business, and here we remain, now even deeper into autumn. We have delved into its history, all twelve villages in the municipality, all eight ancient monasteries, suffered its sorrows, and mourned its wounds. We have described the thorns and gifts, geological layers, and old trees in the forest.

We stopped by this town this summer for business, and here we remain, now even deeper into autumn. We have delved into its history, all twelve villages in the municipality, all eight ancient monasteries, suffered its sorrows, and mourned its wounds. We have described the thorns and gifts, geological layers, and old trees in the forest.

To all this about Irig, historical and geographical, past and present, we wanted to add another Irig: literary. That Irig, woven from some unforgettable pages of Serbian literature, would be a noble treasure here. That’s why, while preparing our monograph, we also made a chrestomathy ”Irig in Literature”. A song from Zmaj, and some prose pages by Milorad Popović Šapčanin, and a text by Jovan Grčić, and a description from Crnjanski were also found there... Dositej Obradović’s embellished notes about Hopovo and Irig, the moving diaries of Milica Stojadinović Srpkinja from 1854, and Mihiz’s chapters from Irig were indispensable. But that intention outgrew itself in our eyes and the volume of the chrestomathy became a special book. While we wait for its appearance, we will mention here something like a pinch of the finest spice.

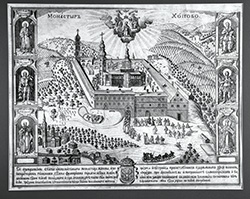

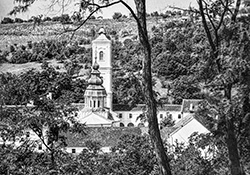

”... Hopovo was in our hearts; we went to it in vain. Around noon we arrive in Irig and head to the monastery. As Todor, a hat maker, told us, when we cross the monastery land, it seems to us as if we have come to the Garden of Eden”, describes Dositej Obradović in the work Life and Adventures (Leipzig, 1783). ”You go all the way past a stream, next to which there are large walnut trees and other trees that shade it and protect it from the sun. On the left side, you can see hills and hillocks, covered with vineyards and orchards. On the right side of the stream stretched out a pleasant valley, all covered and decorated with meadows full of grain and flowers of the countryside, which stretched near the monastery, and on the other side of the valley, I would say the royal gardens. Vineyard after vineyard, surrounded and adorned with all kinds of fruitful trees, hill upon hill and holm upon holm, as if one was leaning on the other lovingly, and as if one on top of the other begged its proud head to make that beautiful valley, its sister, and the stream, her lover who is holding her in his arms, and those who pass by him, to look at and consider...

”... Hopovo was in our hearts; we went to it in vain. Around noon we arrive in Irig and head to the monastery. As Todor, a hat maker, told us, when we cross the monastery land, it seems to us as if we have come to the Garden of Eden”, describes Dositej Obradović in the work Life and Adventures (Leipzig, 1783). ”You go all the way past a stream, next to which there are large walnut trees and other trees that shade it and protect it from the sun. On the left side, you can see hills and hillocks, covered with vineyards and orchards. On the right side of the stream stretched out a pleasant valley, all covered and decorated with meadows full of grain and flowers of the countryside, which stretched near the monastery, and on the other side of the valley, I would say the royal gardens. Vineyard after vineyard, surrounded and adorned with all kinds of fruitful trees, hill upon hill and holm upon holm, as if one was leaning on the other lovingly, and as if one on top of the other begged its proud head to make that beautiful valley, its sister, and the stream, her lover who is holding her in his arms, and those who pass by him, to look at and consider...

No one knows how to pass through that blessed valley, or how to get to the monastery. And when we come to my beloved Hopovo, what will one look at first, what will one consider? What will they admire and wonder about more? If I were all eyes, and if I could look at all sides at once, I would not have seen that beauty... Open this eternal book at any time... By reading this same book, without any other, Melchizedek became a priest of the highest god... He who does not see this book is blinder than one born blind; he who does not hear its voice is deafer than a blue stone... Here, my dear reader, the thoughts of the beauty of Hopovo elevate my mind. Oh, a place worthy to be dedicated to wisdom and learning and to call yourself the Serbian Parnassus!”.

THE DIARY OF VRDNIK

Milica Stojadinović Srpkinja kept her poetry diary full of admiration for her homeland and tenderness for the Serbian fatherland for five months in 1854. It was published in Novi Sad and Zemun, in three volumes (1861, 1862, 1866).

Milica Stojadinović Srpkinja kept her poetry diary full of admiration for her homeland and tenderness for the Serbian fatherland for five months in 1854. It was published in Novi Sad and Zemun, in three volumes (1861, 1862, 1866).

”... Just as the sun was turning to night, I returned home from Vienna, where I traveled with my brother and sister-in-law a few weeks ago; and now I can say that the moment in which a person returns to its homeland is blessed. Care and longing for one’s own then overflow into one feeling – a feeling of joy, which cannot be adequately expressed in words”, she wrote at the beginning of May 1854.

Thoroughly describing her village life, work and days, festivals, cherry picking during which the girls sing and she writes down harvest songs in the shade, the celebration of Sošestivija and Vidovdan, the arrival of Serbs from all over to kiss the relics of their Holy Prince and receive a blessing, a multi-day stay of the exhausted Vuk Karadžić in Stojadinović’s house, a visit by the Serbian Patriarch, her reading days and nights, correspondence with important contemporaries... On the feast of Saints Constantine and Helena, she returns from Šid, where she accompanied Vuk on his return to Vienna, and writes:

”One hour ago, I returned to my home from my relatives from the North of Vojvodina, where I said goodbyes to Mr. Vuk, and everyone said goodbye with the desire to see him alive among us again. (...) I will gladly remind myself of that beautiful road through the flat green fields of Srem, past the chain of wonderful ‘Fruška Gora’ hills, and the continuous view of the mile-long hills of Serbia that were blue from the south. I was often overcome by poetic desires...”

”One hour ago, I returned to my home from my relatives from the North of Vojvodina, where I said goodbyes to Mr. Vuk, and everyone said goodbye with the desire to see him alive among us again. (...) I will gladly remind myself of that beautiful road through the flat green fields of Srem, past the chain of wonderful ‘Fruška Gora’ hills, and the continuous view of the mile-long hills of Serbia that were blue from the south. I was often overcome by poetic desires...”

And on June 8 (according to the Julian calendar), in the evening:

”From there, I go to the vineyard to bring cherries. Bending the native branches, I look at the waters of the Sava, across which the Mačva Plain and the Cer Mountain are blue; but Cer is so beautiful to see, and so close, that you think you can see the flickering of the leaves, which is a sign for the locals that there will be rain...”

She persistently writes down folk songs, proverbs, and stories, and sends them to Vuk.

”While my maids were weeding onions, parsley, and other things, I didn’t let them rest from singing, because I wanted to collect as many songs and other charms as possible; I know for sure that the three collections published by the excellent Vuk did not include all the folk songs, and that there would have been three more books, only if another Vuk had been found, or if this worthy old man had lived that long...”

IN THE JAWS OF MEMORY

Mihiz is a special story or movie. As much as he was born in Irig, it is also the other way around. It is difficult to extract anything from his pages from Irig because everything should be as it is. And Autobiography About Others, which Milo Gligorijević pulled out from him, begins with the chapter ”Homeland”.

Mihiz is a special story or movie. As much as he was born in Irig, it is also the other way around. It is difficult to extract anything from his pages from Irig because everything should be as it is. And Autobiography About Others, which Milo Gligorijević pulled out from him, begins with the chapter ”Homeland”.

”In my birthplace, there was neither a river nor a real pond, not even a virtuous stream. I guess that’s why, even though I’ve lived in Belgrade for more than four decades, I rarely go down to its rivers and I don’t understand well, and I don’t like water...” he writes. ”All my ancestors, as far as the family chronicle goes back and remembers, both on my father’s and my mother’s lines, were from Srem. There is not a single daughter-in-law from Bačka or Banat, or a son-in-law from another part of Serbia, or from Slavonia. All were from Srem.

In the obituary that I inherited from my father, six generations of my ancestors were noted: three priests, and before them three artisans, poulters, and furriers. Mother brought her farmer ancestors into the family. My farmers, poulters, and priests lived and died all over the vastness of Gornji Srem and Donji Srem, in Vukovar, Bingula, Čalma, Ledinci, and Irig, where I was also born”.

In the obituary that I inherited from my father, six generations of my ancestors were noted: three priests, and before them three artisans, poulters, and furriers. Mother brought her farmer ancestors into the family. My farmers, poulters, and priests lived and died all over the vastness of Gornji Srem and Donji Srem, in Vukovar, Bingula, Čalma, Ledinci, and Irig, where I was also born”.

Irig is a special section in the Autobiography, just like the natives of Irig.

”Several years ago, when my play Commander Sajler was performed in Vienna, at the reception given to me by the polite and ceremonial hosts from the Volkstheater and the Austrian Penn, I quoted a mockery with which my countrymen mock us people from Irig:

Natives of Irig every day

Natives of Irig every day

Pray to God for a railing,

To make their way to Vienna,

To sell some limestone.

I added that even to this day, the people from Irig have not reached ‘the railing’, and here I am, here, in Vienna to sell them some of my intellectual limestones.

The trains really bypassed Irig. One, the one from the Danube, from Čortanovci, passed along the banks of the Danube, and the other went down, via Ruma, through the flat Srem, leaving us from Fruška Gora’s ”wine” Srem without ”the railing”.

The people of Irig used to be farmers, winegrowers, traders, artisans, and apprentices. Eager to become independent they learned the trade, so they could sell their goods, and their handicrafts in shops and at fairs. But there were also limestone peddlers. They took out stone and wood from Fruška Gora, slaked lime, carried it around in buckets, and sold it.

That limestone Irig must have been subject to other, more dangerous taunts, when a defensive reflex was created, so when asked: ‘Where are you from?’ – claim the old people of Srem – the residents of Irig answered angrily: ‘From Irig, so what?’ grasping the razor, warning off the sneer with a threat. People of Irig believe that these taunts are pure envy and malice of our insignificant neighbors because of the exceptionality of our place. I myself, probably in a nostalgic bias, am convinced that Irig was not an ordinary Srem settlement”.

That’s what Mihiz, who knew very well that in Irig both defense and attack are made with jokes, wrote. The easy part is on us. To read.

***

Under the Crown of Fruska Gora

The representative monograph ”Irig. Crowned by Fruska Gora” was written and produced in 2022 by the ”Princip Pres” team for the needs of the Municipality of Irig, which was also the main publisher. The book was conceived and edited by Branislav Matić, translated into English by Nataša Vujović, and features photographs contributed by a series of top authors. From there, these pages before you originate.